Learning from the Luddites: Implications for a modern AI labour movement

Published:

The Luddites were a social movement of English textile workers in the 19th century, famous for smashing the machines that were replacing their jobs. The term Luddite is now used to describe opponents of new technologies (often in a derogatory way). However, I believe many people using the term misunderstand what the Luddites did and wanted. Indeed, the Luddites and their ultimate failure can teach a modern AI-labour movement valuable lessons.

In this piece, I will describe the history of the Luddites. The context, their actions and demands, and the response from industrialists and governments. I’ll also discuss the usage of the term Luddite in current discourse and draw lessons from their failure for a modern movement against AI-job displacement.

History of the Luddites

The emergence of the Luddites

In the 18th century, the English textile industry had seen the introduction of the Spinning Jenny and Water Frames. Until then, cottage work was done by skilled workers in their own workshops. But the new machines were capital-intensive and required a centralised power source, thus necessitating the transition to factory production. This meant many textile workers either became unemployed or had to start work in factories for lower wages under horrible working conditions. While textile workers used to be organised in guilds, which ensured them a stable income, it was now illegal for them to organise into labour unions, thus removing their collective bargaining power.

But things were about to get even worse. The 1800s saw the introduction of multiple machines that automated or sped up parts of the textile jobs and could be operated by unskilled workers. Wide stocking frames flooded the markets with cheap, low-quality goods, undercutting skilled framework knitters. Shearing frames automated the finishing of woollen cloth, which was previously done by highly-skilled croppers. But worst, steam-powered looms meant that one unskilled worker could match the output of many hand looms operated by highly-skilled workers. In addition, England’s economic situation was harsh. The Napoleonic Wars drove up food prices and made competition with France the #1 policy objective.

This unlivable economic situation led textile workers to rebel. On March 11 1811, a group of knitters assembled in Arnold, Nottingham, to destroy 63 wide stocking frames. From there, a movement formed. Textile workers started to assemble into well-organised groups. They conducted military training and were intensely secretive. With every further attack and destruction of machines, the movement spread across the country and gained popular support.

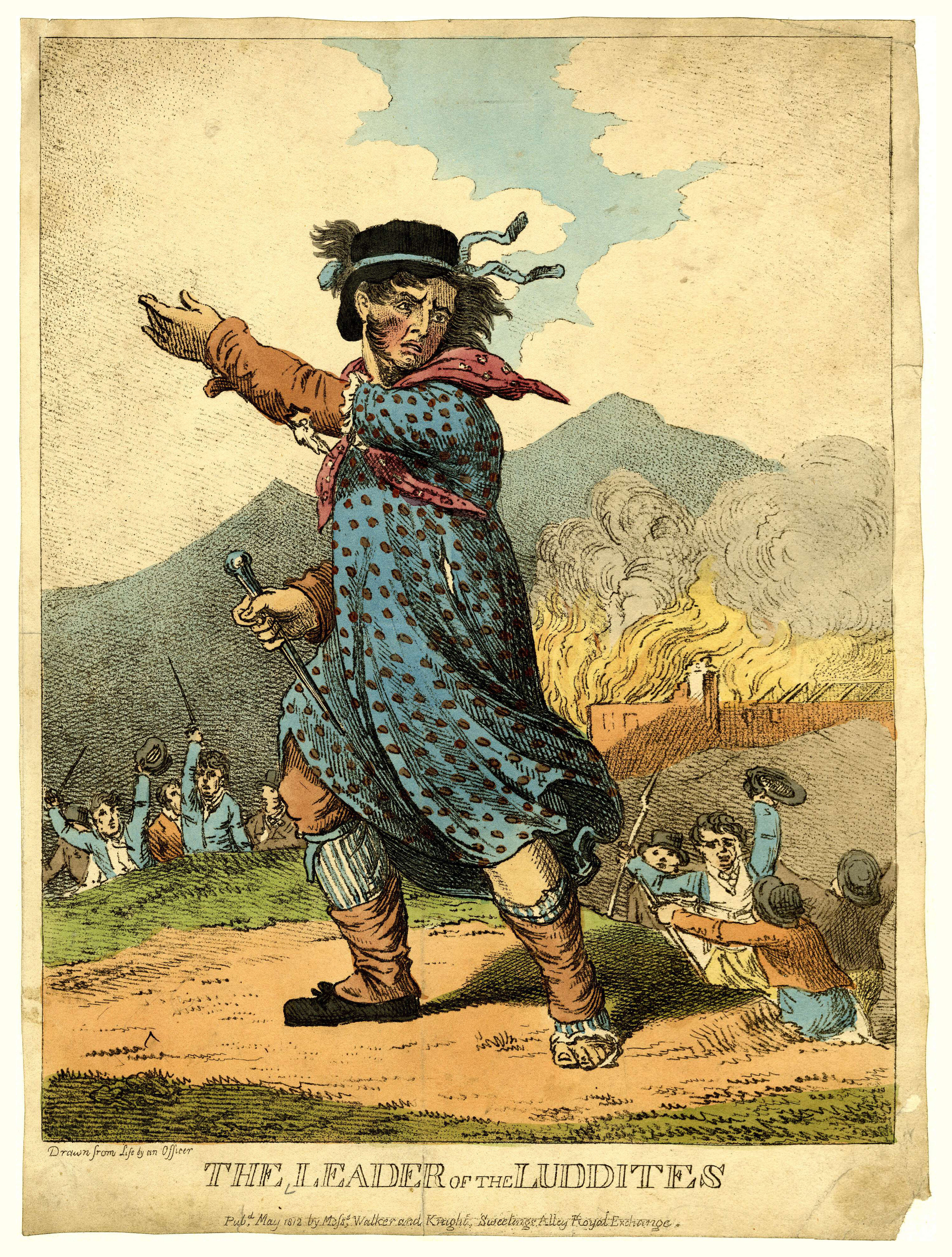

In this environment, the legend of Ned Ludd emerged. He was a worker in a textile factory in 1779 who was instructed to change his methods of production and, in the resulting fit of passion allegedly smashed two stocking frames. The emerging anti-machine movement was named “The Luddites” after him, adopted them as their legendary leader (called General Ludd) and used his name as a pseudonym in letters written to mill owners.

The Luddite Strategy

Contrary to popular belief, the Luddites were highly strategic in their actions. They didn’t indiscriminately attack all machinery - only specific technologies that directly threatened their livelihoods. The Luddites also focused their attacks on particular employers who broke wage agreements and introduced machinery in ways that violated established practices. They would often send letters with demands and only attack if those demands weren’t met. This shows that machine smashing was not (only) an angry reaction, but a bargaining tool for better working conditions.

In addition to machines breaking, the Luddites organised public demonstrations and sent letters to government officials. They also attempted to work within existing systems, using the Company of Framework Knitters - a recognised public body - to negotiate with factory owners. As these channels failed, they escalated to threatening factory owners, their families and local authorities they saw as complicit.

The main grievances of the Luddites included:

- Wage cuts- Employees were fighting for their (economic) survival as wages sank while food prices were skyrocketing. They used collective bargaining to demand higher wages.

- Price cuts - Textile goods were becoming cheaper, reducing the value created by highly-skilled textile workers. They asked local magistrates to enforce price limits.

- Deskilling - As their work was being replaced by low-skill labour they asked employers to protect their jobs during trade depressions.

- Quality standards - They opposed the production of cheap, shoddy goods that undercut the market for quality textiles and degraded their trade. They asked the government to enforce quality standards in textile production.

- Breaking traditional labour practices - Employers were abandoning apprenticeship systems and customary agreements about wages and working conditions. They advocated for the prosecution of employers who violated these norms.

The Reaction

Industrialists reacted by attempting to defend their factories. They started to hire local militia to stay overnight. They barricaded factories and built safe rooms. In a nighttime attack on a factory, a Luddite was shot and killed, causing the movement to turn more violent. One mill owner was ambushed and killed (to be fair, he had said he’d “Ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood”). Those complicit in the murder were hanged. Further violence followed as the battles intensified.

The British Government also stepped in, as it could not tolerate social unrest in a time when competition with France was so tense.

An extremely British assessment of the situation: “The Magistrates have observed with extreme regret, the Spirit of Disorder which has for some time past disgraced the County”

Curfews were enforced, bounties offered to reveal the identity of Luddites and factories got defended. Overall, 12000 government troops were involved in suppressing Luddite activity. Show trials were held to deter further uprising, in which 60 alleged Luddites were charged with various crimes. While some of the defendants had no relation to the Luddites, others were hanged or deported. In 1812, the parliament passed the Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812, which set the death penalty for machine breaking (not to be confused with the Protection of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1788, which merely warranted deportation). Overall, these interventions were effective and the Luddite movement started to die down after 1813 and was effectively crushed by 1816.

Current use

Luddism still exists in current discourse. Some have started to embrace the term for themselves, calling themselves neo-Luddites. They favour technological minimalism, “resist consumerism and the increasingly bizarre and frightening technologies of the Computer Age”. In economics, the “Luddite Fallacy” refers to the mistaken belief that new technology causes permanent unemployment. Instead, technology may disrupt some jobs, while creating new ones elsewhere, keeping overall employment stable. (This offered little comfort to the original Luddites, who did face unemployment, deskilling, and a shift to lower-wage factory work with horrific conditions.)

However, “Luddite” is mostly used as dismissive name-calling for people raising concerns about the development of new technologies. In the AI discourse, “Luddite” is not only raised against people resisting the adoption of AI, but also against those opposing the development of superintelligent AI or even against advocates for AI Safety. Sometimes these are referred to as “Yuddites” in reference to Eliezer Yudkowsky (which is admittedly a funny wordplay).

The term carries connotations of a narrow-minded resistance to change, a general pessimism about technology and the inevitability of technological development, which makes resistance futile. However, it is understandable that the Luddites had to fight for better working conditions as their livelihood was a stake. Furthermore, they were actually correct about the negative effects of this technology on their livelihoods and working conditions. Lastly, they were likely aware that they couldn’t fully revert to a “time before the machines”. Instead, they tried to negotiate higher wages, job security and product quality within the new production environment.

Lessons for a Modern AI Labour Movements

There are clear parallels between textile automation and job loss from AI: skilled workers facing displacement by technology that can perform their tasks faster and cheaper, operated by less-skilled labour or no labour at all. Additionally, this happens in the context of fierce international competition.

While the Luddites were more strategic and sophisticated than they are often given credit for, they still failed to achieve their objectives. What can we learn from their failure?

Making conclusions based on history is fraught. You shouldn’t believe these points just because there is a historical example for them.

What we shouldn’t take away from this

First, there are 2 lessons commonly taken from the Luddite History that I think won’t hold for AI (esp AGI):

- You cannot resist technological advancements; the current is too strong. Yes, stopping the advancement of AI will be difficult. But as we are early in the adoption of this technology, we can shape the development, use our leverage to negotiate concessions and overall influence the trajectory of the technology.

- Job automating from new technologies is fine as other jobs emerge elsewhere (The Luddite Fallacy): AGI might be different, as it could replace ~all human labour. Additionally, job replacement is still often economically ruinous for those affected.

Additionally, AI will differ in many ways from the Industrial Revolution. Among other differences, the pace of development and adoption of AI is higher; it might affect more sectors at the same time than machinery and the societies into which these technologies are born differ fundamentally.

What can we learn from the Luddites?

Timing matters: The Luddites organised after their displacement had already begun, and they had started to lose their negotiating leverage. Today’s AI-affected workers still have power: the technology is not yet fully deployed, companies still need human expertise to build and refine AI systems, and the economic transition hasn’t yet occurred. This window won’t last. Thus, workers need the foresight to protest and negotiate before their jobs have been automated.

Geopolitical context matters: The strong intervention by the British Government was partially explained by not wanting social upheaval to start at a time of fierce competition with France. Similarly, the race for AGI between the US-China will likely intensify at the same time as more jobs will be displaced. As the development and deployment of AI will become one of the highest policy priorities of those countries, they might look less favorably on the resistance against AI by workers. This could plausibly (esp in the more authoritarian countries) cause the government to crack down on such protests against AI adoption.

Organised Labour allows for collective bargaining: The Luddites reverted to violent means as a bargaining strategy, partially because labour unions were forbidden, which cut off some less violent negotiating tactics. For professions that are at risk of AI-induced job loss, it might be especially valuable to organise labour unions. Additionally, it could be advantageous to build some legal “moat” around your profession by, eg getting laws passed that require doctors to be humans.

Movements don’t just happen: The Luddite movement did not simply spring from the economic conditions. It was built through the courage, organisation and agency of its participants, with some even giving their lives. While AI movements hopefully will not require such sacrifices, it will still require dedicated effort, good strategy and the courage to speak out on your beliefs.

Movements need iteration: The Luddites were a “transitional movement”. Their efforts did not directly lead to better working conditions. But by developing class consciousness, exploring methods of political influence and building a moral economy. On this foundation, later working-class movements did achieve success in gaining better working conditions and legalising trade unions. Similarly, any AI movements should not expect to succeed on the first try. Instead, early movements will likely develop the public awareness, moral framework and political levers that later movements can be built upon.

How would you even smash the machines?

If an AI-labour movement were to turn to destructive resistance, it is unclear what they would do. (I am not advocating for this, but want to map the analogous actions workers could take today.)

- Smashing the datacenters is certainly one option, but it only destroys some GPUs, while AI models can continue running on other servers. Additionally, anonymous, physical attacks are less viable than they were in 1811 due to modern surveillance and digital forensics.

- Physically attacking the company leaders or AI developers is also an ill-advised tactic. When the Luddites turned to murder and violence, public sentiment turned against them. (Also in general it’s evil to hurt people!)

- More sophisticated actors could attempt to sabotage internal AI services. This could be hacking attacks to sabotage workflows, destroy other company-internal digital infrastructure or even delete model weights.

- Finally, the data produced by workers could be used to train AI models that will then replace them. Workers might intentionally poison the data to reduce the AI’s performance and maintain their jobs. This is akin to some factory workers manipulating machinery and not pointing out inefficiencies.

What an AI-labour movement could do

Unlike the Luddites, today’s workers have advantages: democratic representation, the ability to organise legally, and broader public sympathy before displacement occurs. Rather than trying to stop AI entirely, affected workers could negotiate the terms of its deployment. This could include profit-sharing arrangements, universal basic income funded by AI productivity gains, mandatory worker representation on AI company boards, or robust transition support and retraining programs. The Luddites asked for wage protections, quality standards, and job security within the new industrial system - they tried to shape how technology was implemented, not prevent progress itself. Modern workers should learn from both their strategic insight and their tactical failure: negotiate now, from a position of strength, rather than waiting until the leverage is gone.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ned_Ludd

The Making of the English Working Class - E. P. Thompson

Claude

Chapter 24: The Luddites - The Industrial Revolutions